Indexes

The building blocks of database performance

Indexes are an entirely separate data structure that maintain a copy of part of your data. When you create an index, it creates a second data structure, which is different from your primary data structure (the table). It's crucial to understand that each index maintains a copy of part of your data, which means that if you have multiple indexes, there will be multiple copies of different parts of your data.

Moreover, indexes have a pointer back to the row. It's necessary for an index to know how to get back to the table because it maintains a copy of part of your data.

Unlike schema design, you cannot look at your data and decide what indexes to put on your table. Instead, you have to examine your queries to determine which indexes will perform the best. In other words, indexing should be driven by the access patterns of your application.

Rules for creating indexes

As far as the rules for creating indexes are concerned, you should aim to create as many indexes as you need. Indexes are the best tool for creating a performant query, which usually translates into a performant application. However, you should also create as few as you can get away with because creating too many indexes can impact the performance.

It's essential to strike a balance between how many indexes you need and how few you can get away with. Establishing this balance depends on the size of your database, frequency of updates, and other factors that might influence the performance of your application. With that in mind, it's crucial to look at access patterns when deciding which indexes to create.

B+ trees

Indexes speed up data retrieval. Without an index, MySQL would have to read through the entire table to find a specific value.

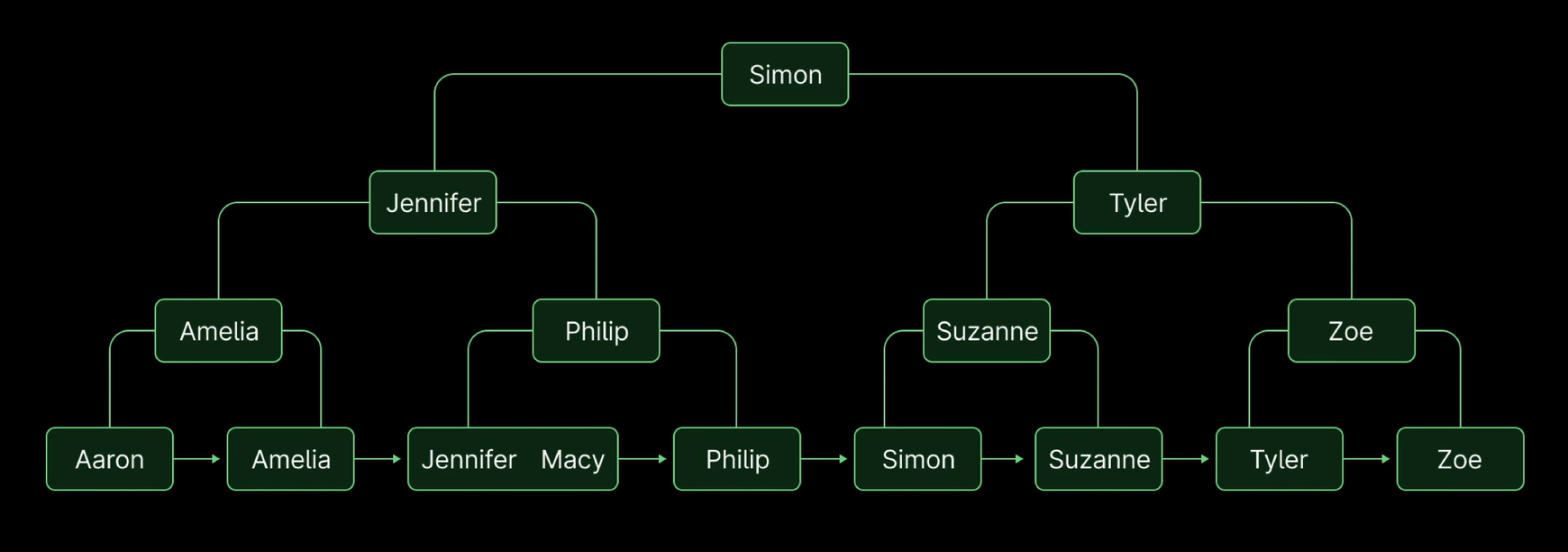

This data structure resembles a tree structure with nodes, and it functions as a map for accessing specific data in a table. To demonstrate how B+ trees work, let's visualize an index on the people table. You can see that it looks like a tree, with the root node at the top and the leaf nodes at the bottom.

The root node isn't very relevant to us right now, so we'll shift our focus to the leaf nodes. Each name in the table has its own corresponding node in the B+ tree. The leaf nodes contain the data that we have indexed, in this case, first names.

Searching

It is just tree binary search.

Let's assume we want to search for the name "Suzanne."

Starting at the root node, we'll compare "Simon" to "Suzanne." As "Suzanne" is later in the alphabet than "Simon," we'll head down the right side of the tree. We'll then compare "Tyler" to "Suzanne." Since "Suzanne" comes before "Tyler," we'll head down the left side. We'll find the node with the name "Suzanne" and compare it to itself. Since the values match, we'll head down the right side of the tree and land where we want to be.

This algorithm allows us to skip over many of the leaf nodes at the bottom and only look at a few nodes. Without an index, we'd have to read through every single row to find the name "Suzanne."

B+ trees build up a secondary data structure that optimizes searching for specific values. By creating an index on the first name field, we've optimized this secondary data structure for searching first names.

Primary keys

A primary key is a unique identifier for each row in the table, and it plays an important role in how your data is stored and accessed.

Keep in mind that while this is the simplest method, there are some things to be aware of. For example, MySQL will automatically make the primary key column not nullable, and it will create a unique index for the column. This means that you don't need to create a separate index for the primary key, and doing so could result in duplicated indexes.

primary keys vs. secondary keys

A secondary key is any index that is not the primary key. It's used to improve performance when searching for specific data in your table.

A primary key, on the other hand, is a unique identifier for each row in the table.

Why choosing the right primary key matters

The primary key determines how your data is stored on disk. In MySQL's InnoDB engine, the primary key is a "clustered index," which means that the data is physically ordered based on the values in the primary key column. This makes primary key lookups incredibly fast, but it also means that every time you insert a new row the tree structure has to be updated.

Choosing a good primary key is important because it can impact the performance of your queries. For example, using a GUID or hash as a primary key can be slow because it requires more storage space and can lead to slower insert performance as the tree has to be rebalanced. On the other hand, using an auto-incrementing integer as a primary key can be more efficient because it requires less storage space and new values always go at the end.

Secondary keys

Secondary key (also known as indexes) is any key (or index) that is not the primary key. It has a special relationship to the primary key.

A secondary key is simply any index that is not the primary key of a table. Every MySQL table has one primary key and can have multiple secondary keys. It is crucial to note that primary and secondary keys are still related to each other, and understanding this relationship is crucial to working with them effectively.

Example:

Consider a people table with the columns id, name, and email. We can create a secondary key on name using the following MySQL query:

An index on the name column is now created, and we can use it to query the people table.

Here is a sample query that retrieves all the rows of a person whose name is Suzanne using the secondary key:

How the query works

When executed, MySQL uses the B-tree index created on the name column to locate the row with the specified name. It begins at the root node of the index and works its way down through the branches until it reaches the leaf node representing the row with the matching name.

Now, since the name column is a secondary key, it does not store all the data required for the query. It only contains the indexed column name and a pointer to the rest of the row. MySQL must perform a second lookup to retrieve the rest of the data related for that row.

Every secondary key has the primary key appended to it, as each leaf node in the secondary key contains a pointer back to the row. When you perform a query with a secondary key, MySQL first traverses the secondary index tree, finds the corresponding primary key, and then looks up that primary key in the primary index tree to retrieve all the data.

Importance of compact primary keys

As previously mentioned, each leaf node in a secondary key has the primary key appended to it. Therefore, it is crucial to choose compact primary keys that require a minimal amount of storage space.

Primary key data types

What data type you should use for primary keys in MySQL

An essential decision when designing a database schema is choosing the data type for the primary key. The primary key serves as a unique identifier for each record in a table, and it is a critical element in database design. As such, it is essential to choose the right data type that meets the database's requirements and avoid potential pitfalls that could lead to performance issues or other problems down the road.

The benefits of unsigned big integers

The recommended practice for primary keys is to use unsigned big integers. Unsigned big integers provide virtually infinite room to grow, which is essential because running out of primary key space is a significant issue for databases. Additionally, they allow for auto-incrementing, which preserves a natural order for the records, ensuring that the primary key B-tree isn't split unnecessarily.

Choosing strings as primary keys

Choosing a string data type, such as a UUID or a GUID, as a primary key can be tempting, but it has potential pitfalls. The problem with these types of data is their size, which means the indexes of the table grow enormously as a result of them. Additionally, the B-tree may have to be rebalanced if insertions occur in the middle of the table.

If you want to use a string as a primary key, you should look for a UUID or GUID that is time-sorted, so all new records go to the end of the table, rather than in the middle. ULIDs are a new option for sorted GUIDs that are worth considering.

Obfuscation of the primary key

Some developers might use UUIDs or GUIDs to obfuscate the primary key when exposed in public APIs or URLs. This approach is not ideal, as the primary keys are better used for unique identification of each record in the database while leaving the obfuscation to a separate column.

Where to add indexes

We've said before that your queries should drive your indexes. What does this mean? It means that you should start by analyzing the access patterns of your application before deciding where to put indexes.

Before adding an index, ask yourself, which queries are you running frequently and which tables are they accessing? By analyzing the access patterns of your queries, you can better determine which indexes will be most useful. Keep in mind that not all queries require indexes, and adding too many indexes can actually harm your database's performance.

Here are some general rules of thumb to consider when deciding whether or not to use an index:

-

Do not assume that anything that shows up in the where clause of a query should have an index. Consider all queries being run and their respective access patterns.

-

Do not create an index on every column. This will slow down inserts by functionally duplicating your table. It also won't help reads as much as you'd hope.

-

Do consider the entire query when deciding which columns to index. This includes sorting, grouping, and joining.

-

Do not worry about trying to create the perfect index for every query. It may not always be possible, and sometimes you will have to rework the queries to take advantage of existing indexes.

This creates an index named birthday_index on the birthday column of the people table.

Example:

Let's take a closer look at how indexes can optimize specific queries. We will be using the people table we used in the previous section, which includes an id, first_name, last_name, state, email, and birthday column.

This query will return the first 10 rows of the people table sorted by the birthday column. Since there is an index on the birthday column, MySQL can use this index for sorting instead of doing a full table scan.

This query groups all people by their birthdays and returns a count of all people born on the same day. Once again, since there is an index on the birthday column, MySQL can use this index to group rows together instead of doing a full table scan.

Index selectivity

Indexing is a crucial aspect of MySQL database optimization. It involves adding indexes to important columns to speed up query performance. The process of selecting the best index for specific database columns can be a bit tricky.

Cardinality refers to the number of distinct values in a particular column that an index covers. When you use the SHOW INDEXES command in MySQL, the cardinality column in the output shows you the approximate total number of unique values in a given index column.

Selectivity, on the other hand, refers to how unique the values in a column are. It is a measure of how selective an index can be in narrowing down results when queried. The higher the selectivity of an index, the better it is for optimizing query performance.

Knowing the concepts of cardinality and selectivity can help us make informed decisions when optimizing database performance. For instance, we can use the information on the selective value of a column to determine whether or not to put an index on it.

Suppose we have a table with a type column that has two possible values, user and admin, with most rows having the value user. In this case, putting an index on the type column may not be the best approach to find rows with type = "user" since most of the rows contain the same value. The index is not highly selective for user, but it is highly selective for admin!

Furthermore, if we're stuck and can't figure out why an index isn't being used, we can check the selectivity of the index in question. If the selectivity is low, it is most likely that MySQL decided to read the table, assuming the index would be slower than a full table scan.

Prefix indexes

By indexing just a part of a string column, you can make the index much smaller and faster. For example, indexing only the first four or five characters of a string reduces the size of the index while potentially maintaining the selectivity.

Prefix indexing is especially suitable for long, evenly distributed, and unique strings, such as UUIDs and hashes.

To create a prefix index in MySQL, you have to specify the prefix length you want to index. Suppose we have a people table with a string column for the first name, and we want to index the first five characters only:

Determining prefix lengths

Now that we know how to create prefix indexes let's determine the ideal prefix length of a column. To determine the prefix length of a column to index, we have to calculate the overall selectivity of the column and compare it to the selectivity of the prefix.

Example:

Let’s consider an example where we have a table with a column first_name, consisting of 3009 unique first names out of 500,000 people. In this case, the selectivity of the column is:

Running the above query gets a selectivity of 0.0060.

Now, we can experiment with different lengths in the LEFT() function to determine the smallest prefix length that provides close to full selectivity. Here's a sample of prefixes you can test:

As you increase the prefix length of columns values, we'll notice that the selectivity will also increase. Therefore, we can determine the ideal index for the column based on the minimum prefix length that achieves close to full selectivity. Ideal prefix length is 6.

Drawbacks of using prefix indexing

Prefix indexes are not suitable for ordering or grouping as the index does not contain the full string value, and therefore cannot be used. This makes it impossible to use a prefix index to sort results by the given column. (You can still sort by the column, but it will not use the index.)

Composite indexes

Composite indexes cover multiple columns instead of having individual indexes on each column.

When you inspect the indexes on the people table, you'll notice the multi index with a sequence in the index column. This sequence indicates the order of the columns in the index, which is crucial for how the index can be used.

Rules for composite indexes

-

Left-to-right, no skipping - MySQL can only access the index in order, starting from the leftmost column and moving to the right. It can't skip columns in the index.

-

Stops at the first range - MySQL stops using the index after the first range condition encountered.

Analyzing index usage

To understand how MySQL uses composite indexes, you can use the EXPLAIN statement.

The EXPLAIN output shows that the multi index is being used, with a key length of 404 bytes. This indicates that MySQL is using both the first_name and last_name parts of the index. If we add birthday to the mix, the key_len jumps to 407.

However, if you change the query to include a range condition on last_name, then the key_len drops back down to 404.

The key length remains 404 bytes, meaning MySQL stops using the index at the first range condition (last_name in this case) and doesn't use the birthday part of the index.

Choosing the right order for columns in a composite index depends on the access patterns of your application. Consider the following tips when defining composite indexes:

-

Equality conditions that are commonly used would be good candidates for being first in a composite index.

-

Range conditions or less frequently used columns would be better candidates for ordering later in the composite index.

Composite indexes can significantly improve the performance of your database queries. Understanding and effectively using them is essential for advanced database users. Remember to consider your access patterns and carefully define the order of your columns to create efficient composite indexes.

Covering indexes

A covering index is a regular index that provides all the data required for a query without having to access the actual table. When a query is executed, the database looks for the required data in the index tree, retrieves it, and returns the result. This eliminates the need for the engine to access the actual table, saving a secondary traversal to gather the rest of the data.

For an index to be considered a covering index, it must have all the data needed for a particular query. This includes the columns being selected, the columns being filtered on, and the columns being used for sorting. If an index satisfies all of these requirements, it is said to be a "covering index" for that query.

Covering indexes are powerful tools that can significantly improve query performance. However, they are not suitable for all situations.

Functional indexes

Function-based indexes are used in cases where you need to create an index on a function rather than a column.

For example, consider a scenario where you need to retrieve all the records where the birth month is February. You might have a birthday column in your table, but applying a function such as month() to it will not allow you to use an index. This is where function-based indexes come in handy.

Example: create an index to retrieve records where the birth month is February

In the above SQL statement, we are creating an index called idx_month_birth on the results of the MONTH(birthday) function. The double parentheses are used to denote that we are creating a function-based index.

Indexing JSON columns

MySQL doesn't support indexing JSON blobs.

How to index JSON in MySQL:

- generated columns

- function-based indexes

We need to index email address inside the JSON blob.

Method 1: generating a column

This method works in MySQL 5.7 and 8. Here's how it works:

- Alter the table to add a new generated column. We'll call it email and make it VARCHAR(255).

- Index the new email column.

Step 1: Alter the table:

Here, we're using the GENERATED ALWAYS AS syntax to create a computed column that extracts the email key from the JSON blob.

Step 2: Index the new column

Now that we have generated and indexed the new column, we can use it to quickly find rows based on their email value.

Method 2: Function-based index

This method only works in MySQL 8. Using this method we skip the intermediate column and put an index directly on the function itself.

Here, we're using the CAST function to turn the JSON extract into a CHAR(255) value that can be indexed and setting the collation to utf8mb4_bin.

If you do not collate, it may collate to something else, and you will not receive value with index.

Indexing for wildcard searches

Searching for part of a column using wildcard characters can be useful when you want to find all rows that contain specific words or phrases.

Let's say we want to search for all rows where the email column starts with the name "aaron." We can use the LIKE operator and the % wildcard character to find all matches:

This query will return all rows where the email column starts with "aaron." The % character matches any sequence of characters, meaning that we don't care what comes after "aaron."

If we plan on running this query frequently on a large table, we'll want to add an index to speed up the search. We can add an index to the email column by running the following command:

Now, if we run the same query and use the EXPLAIN command to see how MySQL is executing the query, we should see that MySQL is using our newly-created index:

Querying for specific words or phrases

It's important to note that MySQL can only use an index up until it reaches a wildcard character, such as %. If we want to search for specific words or phrases within a larger column, we need to be careful with how we structure our queries.

For example, let's say we want to find all rows where the email column contains the word "aaron" anywhere within the column:

This query will return all rows where the email column contains the word "aaron" anywhere within the column. However, since we have a wildcard character at the beginning of the search string, MySQL cannot use the index we created on the email column. This means the query will be slower than if we had used a wildcard character only at the end of the search string.

Searching by domain

If we want to search for rows based on the domain of the email address, we may be tempted to put the wildcard at the beginning of the string. However, as we mentioned earlier, MySQL cannot use an index when a wildcard character is at the beginning of a search string.

To get around this limitation, we can create a generated column that stores only the domain of the email address, and then create an index on that column. This allows us to perform a strict equality check, rather than a wildcard search.

For example, we can create a email_domain column that extracts the domain from the email address:

Then, we can add an index on this column and perform a search like so:

By creating a generated column and indexing it, we can perform more efficient searches on specific parts of larger columns.

While B-tree indexes work well for wildcard searches at the end of a search string, they may not be sufficient for more complex text searches. In these cases, we can use a full text index.

Full text indexes allow us to search for specific words or phrases within a larger text column with much greater efficiency than using a simple wildcard search

Fulltext indexes

To add a full-text index to a table in MySQL, you can use an ALTER TABLE statement. In this example, we'll be adding a full-text index across the first_name, last_name, and bio columns in our people table.

Note the use of the FULLTEXT keyword to create a full-text index instead of a regular B-tree index.

Creating a full-text index can take some time, so be prepared for it to take longer than a regular index. You can check that the index was created successfully by running SHOW INDEXES FROM people; which should display the new full-text index.

With the full-text index in place, we can start implementing full-text searches.

Natural language mode

By default, full-text searches in MySQL are done in natural language mode. Natural language mode matches the search query against the indexed columns and returns the most relevant results.

For example, to search for all people with the first name "Aaron," we can use the following query:

This query will search across all three indexed columns and display all rows where "Aaron" appeared.

Boolean mode

For more advanced full-text searches, you can switch to boolean mode. Boolean mode allows you to use modifiers, like +, -, >, <, and parentheses in your search query.

Here's an example of a boolean search query:

This query will search for all rows where "Aaron" appears and exclude any rows where "Francis" appears. The + indicates that "Aaron" is a required search term, and the - indicates that "Francis" is excluded.

In boolean mode, you can also add quotation marks to search for an exact phrase or use the NEAR operator to search for words within a certain distance of each other.

Sorting results by relevancy

When using natural language mode, MySQL automatically orders the results by their relevancy score, with the most relevant result at the top. However, in Boolean mode, you need to manually sort the results.

Luckily, MySQL returns the relevancy score as part of the search query results. You can use this score to sort the results using an ORDER BY statement.

Invisible indexes

There are times when you need to drop an index due to its inefficiency or because it's no longer used by your queries. However, before you do so, you get nervous and start thinking, "What if I've missed something?" Making an index invisible allows you to monitor how your queries perform without the index without having to rebuild it. If everything goes well, you can drop the index. But if something goes wrong, you can quickly turn the index back on without any hassle. Thus, making an index invisible reduces the risks and potential complications of dropping an index.

Making an index invisible enables you to test your queries without risking data loss or any adverse impact on system performance. Once you make an index invisible, MySQL will stop using it in any queries, but it will still maintain this index's integrity. If something goes wrong during testing, it's easy to revert back to the original index state.

You can monitor your system's performance with minimal to no effect on your workflow. Once you are confident of your system's stability with the invisible index, you can fully drop the index.

Making an index invisible is a straightforward process in MySQL:

This command makes the email_idx index invisible so that it is no longer used in any queries.

To verify that the index is invisible, you can use the show indexes from table command again. This time, you'll notice that the email_idx index still exists, but its "Visible" column is set to "NO."

If you want to use the index again, you can revert it back to its visible state using the "alter index index_name visible" command.

This command makes the index visible again so that MySQL uses it in queries.

Duplicate indexes

Not all indexes are created equal, and some may end up being redundant. To prevent duplicate indexes from occurring in the first place, it's important to keep an eye out for indexes that have overlapping leftmost prefixes.

To start, let's take a look at an example of duplicate indexes. Suppose we have a table called people, and we create two indexes:

If we run SHOW INDEXES FROM people, we'll see that we now have two indexes, first_name and full_name.

Based on what we've learned so far about composite indexes, we know that the full_name index covers the first_name index, since the first key part of the full_name index is first_name. Therefore, the first_name index is redundant and can be safely removed.

However, it's important to note that when we add an index on a column in InnoDB, we're really adding an index on column_name and id. Similarly, when we add an index on multiple columns, we're actually adding an index on column_1_name, column_2_name, column_3_name, and id. This is because InnoDB always appends the primary key to the leaf nodes of each index.

Handling redundant indexes

To remove a redundant index, we can use the following code:

This makes the index invisible to the MySQL query planner, effectively removing it without deleting it. Now, when we run a query, MySQL will happily use the full_name index and won't even consider the first_name index.

However, it's important to note that removing a redundant index can have unintended consequences, especially if you depend on the ordering of the rows in that index. For example, if you run a query like this:

MySQL will use the full_name index for the access pattern, but it will have to manually sort the rows because the id column is all the way at the end of the index. This can have a negative impact on performance, especially for large tables.

Foreign keys

A foreign key is a column or set of columns in a table that references the primary key of another table. This enables related data to be linked together in separate tables.

A foreign key constraint is a condition that ensures the referential integrity of the data by enforcing a relationship between the foreign key and the referenced primary key. This means that the constraint will guarantee that all data references are valid and consistent, preventing data from being added, updated, or deleted in a way that would break the relationships between tables.

It's worth noting that foreign keys can exist without constraints, but constraints are helpful to maintain referential integrity. Constraints also require additional computation to maintain, so at a certain scale, you may need to consider dropping some constraints if they become too costly in terms of performance.

Creating tables with foreign keys

Let's take a look at a simple example of creating two tables with a foreign key constraint. We'll start with a parent table and a child table. Here's the code to create the parent table:

This creates a table parent with a single column id as a primary key. Now let's create the child table with a foreign key constraint that references the parent table:

This creates a table child with two columns, id and parent_id. The parent_id column references the primary key of the parent table using a foreign key constraint. This constraint enforces the referential integrity of the data, ensuring that any data added to the child table is consistent with the data in the parent table.

However, it's important to note that when creating a foreign key constraint, the referenced column must be of the same data type as the referencing column. For instance, if the id column in the parent table is unsigned, the parent_id column in the child table must also be unsigned. Additionally, the length and character set of string columns used for referencing each other should match for optimal performance.

Modifying data with foreign keys

Now that we have our tables set up with a foreign key constraint, let's take a look at how data can be modified with this constraint in place.

First, let's insert some data into the child table:

This code attempts to insert a record into the child table with a parent_id value of 1. However, since the parent table is currently empty, this will fail because there is no data to reference.

Let's insert a record into the parent table to correct that:

Now that we have a record in the parent table, we can successfully insert a record into the child table:

The foreign key constraint ensures that this data is consistent and reflects a valid relationship between the two tables.

If we try to delete the record from the parent table, we would encounter another issue:

This code attempts to delete the record from the parent table with an ID of 1. Since there is still a record in the child table that references this ID, the foreign key constraint will prevent this deletion from taking place.

To enable cascading deletes or nullifying deleted references, additional options can be set on the foreign key constraint. It is important to consider the scale and impact of these options to avoid unintended consequences such as excessive data deletion or corruption.